Why Do We Need to Care About Seeds?

For a Healthy Supply of Food We Need a Healthy Variety of Seeds

One of the more important decisions a gardener makes each season is what kind of seeds to plant. Should they be open-pollenated? Hybrids? Heirloom varieties? For Gardiner, New York resident Ken Greene, co-owner of the Hudson Valley Seed Library, the question of what we plant has become his mission.

When Greene first launched a seed-saving effort in 2004, there was no definition for what he was doing. A few other individuals or groups were attempting the same thing elsewhere, but not many. At the time, Greene was a librarian at the Gardiner Public Library and thought of seeds as “stories” — each variety as unique and worthy of saving as any culture’s oral history or literature. So, when the Gardiner Library offered to give him some space for his venture, he called it the Hudson Valley Seed Library (HVSL).

“We were making it up as we went along,” he told us recently. Greene added his collection of heirloom seeds to the library catalog so that patrons “could check them out” just as they might a book. The difference? Instead of reading their loaners, they would grow them in their home gardens. And rather than return them by a due date, they would bring in their saved seed from the plants at the end of the season to expand the library’s seed catalog. The program was small but successful and one of the first of its kind in the country.

Four years after he had started the seed library, Greene and his partner, Doug Muller, turned the operation into a “mission-driven, homestead-based small business,” which is what it remains today, operating on a 28-acre farm in Accord, New York, about half an hour from where they started. There are now more than 300 seed-saving businesses and organizations throughout the United States and there is still no single definition that fits all of them. According to Greene, the organizations are a reflection of the communities where they operate. In one community, the effort might be a not-for-profit service whose mission is to preserve a rare collection of seeds. Another might function more like a seed swap. Some offer classes. Others are full-fledged businesses.

The truth is alarming

Why is seed saving so important? Just look at what Greene found out in 2002 when he began asking where his food was coming from while participating in a group that sourced its food from a 100-mile radius.

“It was shocking,” he recalls. “First, it's really hard to find these answers. When you do start finding them, you learn that seed is under corporate control. In particular, it is controlled by multi-national biotech companies and we have been losing varieties of seeds at an alarming rate…I wanted to make sure we didn’t lose our regionally adapted and cultural varieties here. I felt the only way to guarantee that is to share seeds and teach farmers and gardeners to be seed stewards.”

Open-pollinated plants are pollinated by insects, birds, humans, and the natural elements. The seeds will result in plants that are identical to their parents. Heirloom seeds are open-pollenated and have been passed down through multiple generations within a family or community. Hybrid seeds are produced by cross-pollinating plants. In agriculture and gardening, hybrid seeds predominate today, but they won’t produce true if you save the seeds.

When we save seeds, we are literally joining a human chain that dates back to the Stone Age and the very foundation of civilization. Without seeds, there is no food. With heirloom varieties disappearing at an alarming rate, the Millennium Seed Bank Partnership estimates that some 60,000 to 100,000 plant species are now in danger of extinction, roughly a quarter of all plant species. In this era of climate change, biodiversity may be our food supply’s most fundamental safeguard. Choosing open-pollinated and heirloom seeds helps to maintain genetic diversity, preventing the loss of unique varieties and those that aid our long-term survival because of their hardiness and natural disease-resistant traits.

Taking charge of where our food comes from

Only when we control seed can we take charge of our food supply, ensuring that important varieties are not discontinued because they aren’t profitable enough, or are genetically modified by large corporations to favor characteristics such as long shelf life or hardiness for shipping, Greene cautions.

According to a 2013 report by the non-profit Center for Food Safety in cooperation with Save Our Seeds, three agrichemical firms — Monsanto, DuPont, and Syngenta — now control 53 percent of the global seed market. In fact, multinational corporations actually control a whopping 82 percent of the world’s seed market, including 75 percent of the vegetable seed market, according to Silicon Valley Grows, an organization that promotes seed saving in California’s Silicon Valley. Corporations generally select commercial seed because it performs well in different climates with the use of synthetic fertilizers. Using saved seed from the best performing plants in our own regions, however, allows for the development of varieties that are better adapted to our climates and soils. And because large seed suppliers rarely take the time to cull the inferior plants in their crop, their open-pollenated seeds include those from inferior specimens.

At the HVSL’s farm in the scenic Rondout Valley — between the Catskill Mountains and the Shawangunk Ridge — the production and trial gardens now yield hundreds of pounds of seed each year. At the same time, new varieties are studied, and Greene and Muller undertake traditional breeding projects. Carefully timing the planting of different varieties of the same species and covering the plants with commercially available row cover, enables the deliberate propagation of true seed, the best of which is saved. The seed is grown and perfected for three years before HVSL sells it. At any one time, between 25 and 60 varieties of seed are under cultivation.

Oh, yes…the art!

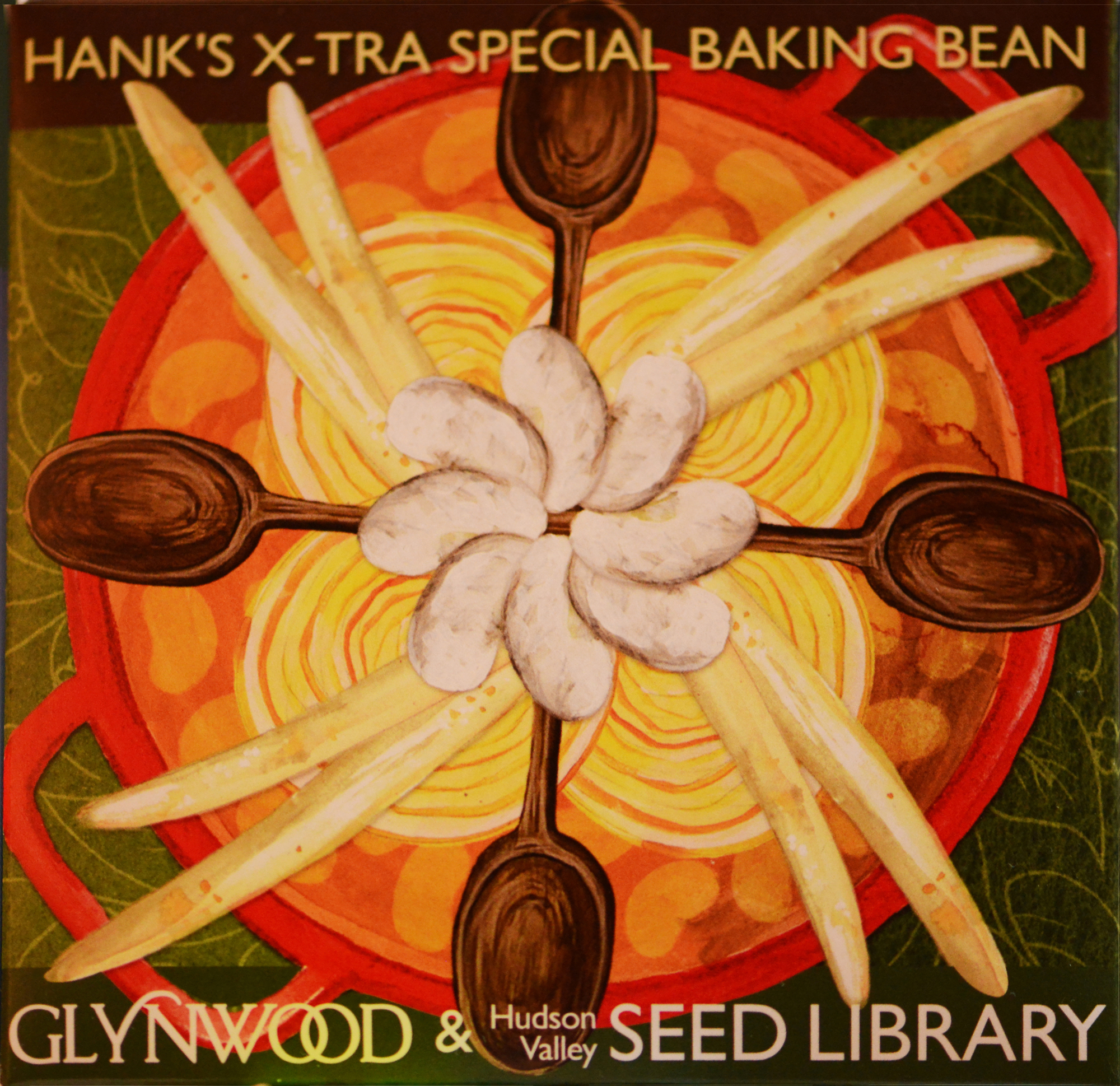

Handle a seed pack or view the catalog (seedlibrary.org) and you can’t help but notice the distinctive square packs bearing the diverse original art that HVSL commissions each year.

Following their annual public call for art, they choose about 20 artists to design and produce a unique work, especially for new varieties. Each artist is matched with a specific variety that Greene and Muller think is suited to the artist’s style. The art styles have included mosaics, ceramics, raku, water color, oils, fiber and interpretive photography. Most artists are from the Northeast. And most are avid gardeners. Each seed’s story is printed inside the pack. The story might describe the importance of the variety in a culture’s history or its spiritual significance in mythology or legend. Greene brings the original art with him to workshops, flower shows, and conferences, setting up on-site galleries and providing tours.

“When you look at a photo of a plant [on a seed pack], you are just looking at the commodity aspect,” says Greene. “When we look at art, we think about the stories.” It's worth noting that if you are looking for an informative and memorable talk as part of a gardening or environmental event, Greene is a terrific presenter. And if you learn that he is lecturing locally, it would be well worth attending.

Greene shies away from taking credit for his impact on the seed saving movement. “I do know we’ve inspired a lot of momentum,” he says, adding that the public has also grown more aware of the dangers of genetic engineering and corporate control of the world’s seed stock in recent years. “For people who are interested in local food, it is really the next step,” he points out. “You get to the point where you begin to ask where your food is coming from. It comes from seed, so where do the seeds come from?”

Anyone can do it

Seed saving practices are not difficult; but they are precise and you need to know what you are doing. Open-pollinated seeds can be challenging because varieties can be cross-pollinated by insects or the wind. Seed-saving techniques include isolating each variety with a barrier such as row cover, staggering plantings so you know that different varieties are pollinating at different times, and allowing enough distance between varieties to prevent cross-pollination, an option that can be difficult for the home gardener. Here at the spiral house, we aren't yet ready to do this ourselves, but we are committed to purchasing seeds from a credible operation like HVSL.

Greene, the horticultural expert of the pair, now travels around the country teaching seed-saving. “You don’t have to be a seed saver to be a seed steward,” says Greene. “If you support an organization like HVSL, you become a seed steward. I’d like gardeners to start thinking about where their seeds are coming from and thinking about themselves as seed stewards.” Look for HVSL’s booth at the next large flower show you attend, like those in Philadelphia and Boston. And, while visiting their site to view their catalog, be sure to sign up for their newsletter to become better informed.

NOTE: Since writing this article, Hudson Valley Seed Library has changed its name to Hudson Valley Seed Company, https://hudsonvalleyseed.com/